James Hannam, God's Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science

(Icon Books, 2009) 320 pages

Verdict?: A superb and long overdue popular treatment of Medieval science 5/5

My interest in Medieval science was substantially sparked by one book. Way back in 1991, when I was an impoverished and often starving post-graduate student at the University of Tasmania, I found a copy of Robert T. Gunther's Astrolabes of the World - 598 folio pages of meticulously catalogued Islamic, Medieval and Renaissance astrolabes with photos, diagrams, star lists and a wealth of other information. I found it, appropriately and not coincidentally, in Michael Sprod's Astrolabe Books - up the stairs in one of the beautiful old sandstone warehouses that line Salamanca Place on Hobart's waterfront. Unfortunately the book cost $200, which at that stage was the equivalent to what I lived on for a month. But Michael was used to selling books to poverty-stricken students, so I went without lunch, put down a deposit of $10 and came back weekly for several months to pay off as much as I could afford and eventually got to take it home, wrapped in brown paper in a way that only Hobart bookshops seem to bother with anymore. There are few pleasures greater than finally getting your hands on a book you've been wanting to own and read for a long time.

I had another experience of that particular pleasure when I received my copy (copies actually - see below) of James Hannam's God's Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science

The Christian Dark Age and Other Hysterical Myths

One of the occupational hazards of being an atheist and secular humanist who has the lack of common sense to hang around on atheist discussion boards is to encounter a staggering level of historical illiteracy. I like to console myself that many of the people on such boards have come to their atheism via the study of science and so, even if they are quite learned in things like geology and biology, usually have a grasp of history stunted at about high school level. I generally do this because the alternative is to admit that the average person's grasp of history and how history is studied is so utterly feeble as to be totally depressing.

So, alongside the regular airings of the hoary old myth that the Bible was collated at the Council of Nicea, the tedious internet-based "Jesus never existed!" nonsense or otherwise intelligent people spouting pseudo historical garbage that would make even Dan Brown snort in derision, the myth that the Catholic Church caused the Dark Ages and the Medieval Period was a scientific wasteland is regularly wheeled, creaking, into the sunlight for another trundle around the arena.

The myth goes that the Greeks and Romans were wise and rational types who loved science and were on the brink of doing all kinds of marvellous things (inventing full-scale steam engines is one example that is usually, rather fancifully, invoked) until Christianity came along, banned all learning and rational thought and ushered in the Dark Ages. Then an iron-fisted theocracy, backed by a Gestapo-style Inquisition, prevented any science or questioning inquiry from happening until Leonardo da Vinci invented intelligence and the wondrous Renaissance saved us all from Medieval darkness. The online manifestations of this curiously quaint but seemingly indefatigable idea range from the touchingly clumsy to the utterly hysterical, but it remains one of those things that "everybody knows" and permeates modern culture. A recent episode of Family Guy had Stewie and Brian enter a futuristic alternative world where, it was explained, things were so advanced because Christianity didn't destroy learning, usher in the Dark Ages and stifle science. The writers didn't see the need to explain what Stewie meant - they assumed everyone understood.

About once every 3-4 months on forums like RichardDawkins.net we get some discussion where someone invokes the old "Conflict Thesis" and gets in the usual ritual kicking of the Middle Ages as a benighted intellectual wasteland where humanity was shackled to superstition and oppressed by cackling minions of the Evil Old Catholic Church. The hoary standards are brought out on cue. Giordiano Bruno is presented as a wise and noble martyr for science instead of the irritating mystical New Age kook he actually was. Hypatia is presented as another such martyr and the mythical Christian destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria is spoken of in hushed tones, despite both these ideas being garbage. The Galileo Affair is ushered in as evidence of a brave scientist standing up to the unscientific obscurantism of the Church, despite that case being as much about science as it was about Scripture.

And, almost without fail, someone digs up a graphic (see below), which I have come to dub "THE STUPIDEST THING ON THE INTERNET EVER", and to flourish it triumphantly as though it is proof of something other than the fact that most people are utterly ignorant of history and unable to see that something called "Scientific Advancement" can't be measured, let alone plotted on a graph.

The Stupidest Thing on the Internet Ever

Behold its glorious idiocy!

(Courtesy of an drooling moron called Jim Walker. Take a bow Jim!)

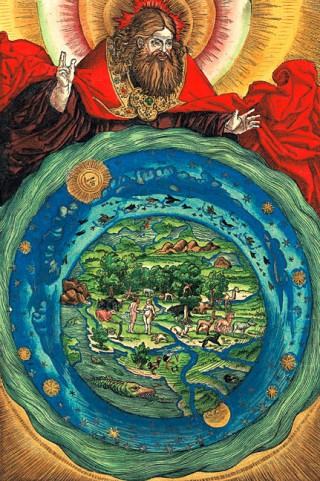

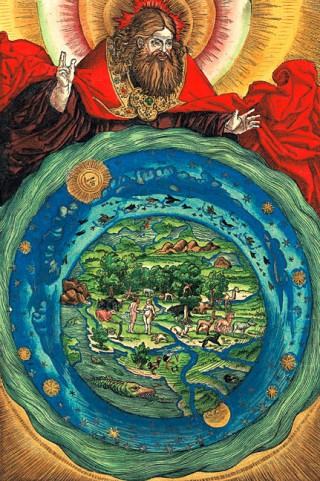

God and Reason

God and Reason

The enshrining of reason at the heart of inquiry and analysis in Medieval scholarship combined with the influx of "new" Greek and Arabic learning to stimulate a veritable explosion of intellectual activity in Europe from the Twelfth Century onwards. It was as though the sudden stimulus of new perspectives and new ways of looking at the world fell on the fertile soil of a Europe that was, for the first time in centuries, relatively peaceful, prosperous, outward-looking and genuinely curious.

It's not hard to kick this nonsense to pieces, especially since the people presenting it know next to nothing about history and have simply picked this bullshit up from other websites and popular books and collapse as soon as you hit them with some hard evidence. I love to totally stump them by asking them to present me with the name of one - just one - scientist burned, persecuted or oppressed for their science in the Middle Ages. They always fail to come up with any. They usually try to crowbar Galileo back into the Middle Ages, which is amusing considering he was a contemporary of Descartes. When asked why they have failed to produce any such scientists given the Church was apparently so busily oppressing them, they often resort to claiming that the Evil Old Church did such a good job of oppression that everyone was too scared to practice science. By the time I produce a laundry list of Medieval scientists - like Albertus Magnus, Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, John Peckham, Duns Scotus, Thomas Bradwardine, Walter Burley, William Heytesbury, Richard Swineshead, John Dumbleton, Richard of Wallingford, Nicholas Oresme, Jean Buridan and Nicholas of Cusa - and ask why these men were happily pursuing science in the Middle Ages without molestation from the Church, my opponents have usually run away to hide and scratch their heads in puzzlement at what just went wrong.

The Origin of the Myths

How the myths that led to the creation of "THE STUPIDEST THING ON THE INTERNET EVER" and its associated nonsense came about is well documented in several recent books on the the history of science, but Hannam wisely tackles it in the opening pages of his book, since it would be likely to form the basis for many general readers to be suspicious of the idea of a Medieval foundation for modern science. A festering melange of Enlightenment bigotry, Protestant papism-bashing, French anti-clericism and Classicist snobbery have all combined to make the Medieval period a by-word for backwardness, superstition and primitivism and the opposite of everything the average person associates with science and reason. Hannam sketches how polemicists like Thomas Huxley, John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White, all with their own anti-Christian axes to grind, managed to shape the still current idea that the Middle Ages was devoid of science and reason. And how it was not until real historians bothered to question the polemicists through the work of early pioneers in the field like Pierre Duhem, Lynn Thorndike and the author of my astrolabe book, Robert T. Gunther, that the distortions of the axe-grinders began to be corrected by proper, unbiased research. That work has now been completed by the current crop of modern historians of science like David C. Lindberg, Ronald Numbers and Edward Grant.

In the academic sphere at least the "Conflict Thesis" of a historical war between science and theology has been long since overturned. It is very odd that so many of my fellow atheists are clinging so desperately to a long-dead position that was only ever upheld by amateur Nineteenth Century polemicists and not the careful research of recent objective peer reviewed historians. This is strange behaviour for people who like to label themselves "rationalists". I'll leave others to ponder how "rational" it is.

Speaking of rationalism, the critical factor that the myths obscure is precisely how rational intellectual inquiry in the Middle Ages was. While dinosaurs like Charles Freeman continue to lumber along claiming that Christianity killed the use of reason, the fact is that thanks to Clement of Alexandria and Augustine's encouragement of the use of pagan philosophy and Boethius' translations of works of logic by Aristotle and others, reason and rational inquiry was one intellectual jewel that survived the catastrophic collapse of the Western Roman Empire and was preserved through the Dark Ages that resulted from that collapse. Edward Grant's superb God and Reason in the Middle Ages details this with characteristic vigor, but Hannam gives a good summary of this key element in his first four chapters.

details this with characteristic vigor, but Hannam gives a good summary of this key element in his first four chapters.

What makes his version of the story more accessible than Grant's rather drier approach is the way he tells it though the lives of key people of the time - Gerbert of Aurillac, Anselm, Abelard, William of Conches, Adelard of Bath etc. Some reviewers of Hannam's book seem to have found this approach a little distracting, since the sheer volume of names and mini-biographies could make it feel like we are learning a small amount about a vast number of people. But given the breadth of Hannam's subject, this is fairly inevitable and the semi-biographical approach is certainly more accessible than a stodgy abstract analysis of the evolution of Medieval thought.

Hannam also gives an excellent precis of the Twelfth Century Renaissance which, contrary to popular perception and to "the Myth", was the real period in which ancient learning flooded back into western Europe. Far from being resisted by the Church, it was churchmen who sought this knowledge out amongst the Muslims and Jews of Spain and Sicily. And far from being resisted or banned by the Church, it was embraced and formed the basis of the syllabus in that other great Medieval contribution to the world: the universities that were starting to appear across Christendom.

God and Reason

God and ReasonThe enshrining of reason at the heart of inquiry and analysis in Medieval scholarship combined with the influx of "new" Greek and Arabic learning to stimulate a veritable explosion of intellectual activity in Europe from the Twelfth Century onwards. It was as though the sudden stimulus of new perspectives and new ways of looking at the world fell on the fertile soil of a Europe that was, for the first time in centuries, relatively peaceful, prosperous, outward-looking and genuinely curious.

This is not to say that more conservative and reactionary forces did not have misgivings about some of the new areas of inquiry, especially in relation to how philosophy and speculation about the natural world and the cosmos could have implications for accepted theology. Hannam is careful not to pretend that there was no resistance to the flowering of the new thinking and inquiry but - unlike the perpetuators of "the Myth" - he gives that resistance due consideration rather than pretending it was the whole story. In fact, the conservatives and reactionaries' efforts were usually rear-guard actions and were in almost every case totally unsuccessful in curtailing the inevitable flood of ideas that began to flow from the universities. Once it began, it was effectively unstoppable.

In fact, some of the efforts by the theologians to put some limits on what could and could not be accepted via the "new learning" actually had the effect of stimulating inquiry rather than constricting it. The "Condemnations of 1277" attempted to assert certain things that could not be stated as "philosophically true", particularly things that put limits on divine omnipotence. This had the interesting effect of making it clear that Aristotle had, actually, got some things badly wrong - something Thomas Aquinas emphasised in his famous and highly influential Summa Theologicae:

The condemnations and Thomas's Summa Theologicae had created a framework within which natural philosophers could safely pursue their studies. The framework .... laid down the the principle that Gad had decreed laws of nature but was not bound by them. Finally, it stated that Aristotle was sometimes wrong. The world was not 'eternal according to reason' and 'finite according to faith'. It was not eternal, full stop. And if Aristotle could be wrong about something that he regarded as completely certainly certain, that threw his whole philosophy into question. The way was clear for the natural philosophers of the Middle Ages to move decisively beyond the achievements of the Greeks.

(Hannam, pp. 104-105)

Which is precisely what they proceeded to do. Far from being a stagnant dark age, as the first half of the Medieval Period (500-1000 AD) certainly was, the period from 1000 to 1500 AD actually saw the most impressive flowering of scientific inquiry and discovery since the time of the ancient Greeks, by far eclipsing the Roman and Hellenic Eras in every respect. With Occam and Duns Scotus taking the critical approach to Aristotle further than Aquinas' more cautious approach, the way was open for the Medieval scientists of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries to question, examine and test the perspectives the translators of the Twelfth Century had given them, with remarkable effects:

(I)n the fourteenth century medieval thinkers began to notice that there was something seriously amiss with all aspects of Aristotle's natural philosophy, and not just those parts of it that directly contradicted the Christian faith. The time had come when medieval scholars could begin their own quest to advance knowledge .... striking out in new directions that neither the Greeks nor the Arabs ever explored. Their first breakthrough was to combine the two subjects of mathematics and physics in a way that had not been done before.

(Hannam, p. 174)

The story of that breakthrough and the remarkable Oxford scholars who achieved it and thus laid the foundations of true science - the "Merton Calculators" - probably deserves a book in itself, but Hannam's account certainly does them justice and forms a fascinating section of his work. The names of these pioneers of the scientific method - Thomas Bradwardine, Thomas Bradwardine, William Heytesbury, John Dumbleton and the delightfully named Richard Swineshead - deserve to be better known. Unfortunately, the obscuring shadow of "the Myth" means that they continue to be ignored or dismissed even in quite recent popular histories of science. Bradwardine's summary of the key insight these men uncovered is one of the great quotes of early science and deserves to be recognised as such:

(Mathematics) is the revealer of every genuine truth ... whoever then has the effrontery to pursue physics while neglecting mathematics should know from the start that he will never make his entry through the portals of wisdom.

(Quoted in Hannam, p. 176)

These men were not only the first to truly apply mathematics to physics but also developed logarithmic functions 300 years before John Napier and the Mean Speed Theorem 200 years before Galileo. The fact that Napier and Galileo are credited with discovering things that Medieval scholars had already developed is yet another indication of how "the Myth" has warped our perceptions of the history of science.

Similarly, the physics and astronomy of Jean Buridan and Nicholas Oresme were radical and profound, but generally unknown to the average reader. Buridan was one of the first to compare the movements of the cosmos to those of another Medieval innovation - the clock. The image of a clockwork universe which was to serve scientists well into our own era began in the Middle Ages. And Oresme's speculations about a rotating Earth shows that Medieval scholars were happy to contemplate what were (to them) fairly outlandish ideas to see if they might work - Oresme found that this particular idea actually worked quite well. These men are hardly the products of a "dark age" and their careers are conspicuously free of any of the Inquistitors and threats of burnings so fondly and luridly imagined by the fevered proponents of "the Myth".

As mentioned above, no manifestation of "the Myth" is complete without the Galileo Affair being raised. The proponents of the idea that the Church stifled science and reason in the Middle Ages have to wheel him out, because without him they actually have absolutely zero examples of the Church persecuting anyone for anything to do with inquiries into the natural world. The common conception that Galileo was persecuted for being right about heliocentrism is a total oversimplification of a complex business, and one that ignores the fact that Galileo's main problem was not simply that his ideas disagreed with scriptural interpretation but also with the science of the time. Contrary to the way the affair is usually depicted, the real sticking point was the fact that the scientific objections to heliocentrism at the time were still powerful enough to prevent its acceptance. Cardinal Bellarmine made it clear to Galileo in 1616 that if those scientific objections could be overcome then scripture could and would be reinterpreted. But while the objections still stood the Church, understandably, was hardly going to overturn several centuries of exegesis for the sake of a flawed theory. Galileo agreed to only teach heliocentrism as a theoretical calculating device, then promptly turned around and, in typical style, taught it as fact. Thus his prosecution by the Inquistion in 1633.

Hannam gives the context for all this in suitable detail in a section of the book that also explains how the Humanism of the "Renaissance" led a new wave of scholars to not only seek to completely idolise and emulate the ancients, but to turn their backs on the achievements of recent scholars like Duns Scotus, Bardwardine, Buridan and Orseme. Thus many of their discoveries and advances were either ignored and forgotten (only to be rediscovered independently later) or scorned but quietly appropriated. The case for Galileo using the work of Medieval scholars without acknowledgement is fairly damning. In their eagerness to dump Medieval "dialectic" and ape the Greeks and Romans - which made the "Renaissance" a curiously conservative and rather retrograde movement in many ways - genuine developments and advancements by Medieval scholars were discarded. That a thinker of the calibre of Duns Scotus could end up being known mainly as the etymology of the word "dunce" is deeply ironic.

As good as the final part of the book is and as worthy as a fairly detailed analysis of the realities of the Galileo Affair clearly is, I must say the last four or five chapters of Hannam's book did feel as though they had bitten off a bit more than they could chew. I know I was able to follow his argument quite easily, but I am very familiar with the material and with the argument he is making. I suspect that those for whom this depiction of the "Renaissance" and the idea of Galileo as nothing more than a persecuted martyr to genius might find it gallops at too rapid a pace to really carry them along. Myths, after all, have a very weighty inertia.

At least one reviewer seems to have found the weight of that inertia too hard to resist, though perhaps she had some other baggage weighing her down. Nina Power writing in New Humanist magazine certainly seems to have had some trouble ditching the idea of the Church persecuting Medieval scientists:

Just because persecution wasn’t as bad as it could have been, and just because some thinkers weren’t always the nicest of people doesn’t mean that interfering in their work and banning their ideas was justifiable then or is justifiable now.

Well, no-one said it was justifiable now and simply explaining how it came about then and why it was not as extensive or of the nature that most people assume is not "justifying" it anyway - it is correcting a pseudo historical misunderstanding. That said, Power does have something of a point when she notes "Hannam’s characterisation of (Renaissance) thinkers as “incorrigible reactionaries” who “almost managed to destroy 300 years of progress in natural philosophy” is at odds with his more careful depiction of those that came before." This is not, however, because that characterisation is wrong but because the length and scope of the book really do not give him room to do this fairly complex and, to many, radical idea justice.

My only criticisms of the book are really quibbles. The sketch of the "agrarian revolution" of the Dark Ages described in Chapter One, which saw technology like the horse-collar and the mouldboard plough adopted and water and wind power harnessed to greatly increase production in previously unproductive parts of Europe is generally sound. But it does place rather too much emphasis on two elements in Lynn White's thesis in his seminal Medieval Technology and Social Change - the importance of the stirrup and the significance of the horse collar. As important and ground-breaking as White's thesis was in 1962, more recent analysis has found some of his central ideas dubious. The idea that the stirrup was as significant for the rise of shock heavy cavalry as White claimed is now pretty much rejected by military historians and his claims about how this cavalry itself caused the beginnings of the feudal system were dubious to begin with. And the idea that Roman traction systems were as inefficient as White's sources make out has also been seriously questioned. Hannam seems to accept White's thesis wholesale, which is not really justified given it has been reassessed for over 40 years now.

- the importance of the stirrup and the significance of the horse collar. As important and ground-breaking as White's thesis was in 1962, more recent analysis has found some of his central ideas dubious. The idea that the stirrup was as significant for the rise of shock heavy cavalry as White claimed is now pretty much rejected by military historians and his claims about how this cavalry itself caused the beginnings of the feudal system were dubious to begin with. And the idea that Roman traction systems were as inefficient as White's sources make out has also been seriously questioned. Hannam seems to accept White's thesis wholesale, which is not really justified given it has been reassessed for over 40 years now.

On at rather more personal note, as a humanist and atheist myself, there is a rather snippy little aside on page 212 where Hannam sneers that "non-believers have further muddied the waters by hijacking the word 'humanist' to mean a softer version of 'atheist'." Sorry, but just as not all humanists are atheists (as Hannam himself well knows) so not all atheists are humanists (as anyone hanging around on some of the more vitriolically anti-theist sites and forums will quickly realise). So there is no "non-believer" plot to "hijack" the word "humanist". Those of us who are humanists are humanists - end of story. And "atheism" does not need any "softening" anyway.

That aside, this is a marvellous book and a brilliant, readable and accessible antidote to "the Myth". It should be on the Christmas wish-list of any Medievalist, science history buff or anyone who has a misguided friend who still thinks the nights in the Middle Ages were lit by burning scientists. But if you don't want to wait that long, keep in mind that I am still giving away a free copy as part of my Armarium Magnum Essay Competition. Entries close at the end of November.

53 comments:

I have browsed Hannam's book but was not convinced that the natural philosophers had as much impact on European science as he thinks they did. For this reason i did not buy it as I felt that the thesis was flawed. I would recommend Anthony Levi's outstanding Renaissance and Reformation : The Intellectual Genesis, Yale ,2002, for an analysis of how medieval thinking far from acting as a springboard for modern science had come to an intellectual deadend.On my brief reading of Hannam, Levi seems vastly more scholarly.

I truly envy and admire people who have the amazing ability to assess books without having read them. I wish I had this magical power, as it would make writing this blog so much easier. Alas, because I don't have this astounding ability, I'm forced to do it the old fashioned way and actually read the book in question.

Perhaps bookworm could explain how science in the Middle Ages "had come to an intellectual deadend" and what, via his total lack of reading of Hannam, Hannam got wrong and what is "unscholarly" about what he wrote.

This should be fun. I'll go make some popcorn while we wait ...

Looking at the reviews of 'Renaissance and Reformation : The Intellectual Genesis' I can't for the life of me see how it relates to Medieval Natural Philosophers and question of whether their work may or may not have fed into the (so called) scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries. It appears to be about the Humanist ideal of the dignity and moral vision of man and it's roots in the crisis of Medieval philosophy.

I await bookworm's response with baited breath.

I think that we don't have to say that Renaissance thinkers were stupid in order to rescue the forgotten medieval ones; we ought to be able to recognise both. But never mind that: what I wanted to ask is if there's a 'quick fix' revision of White on stirrups and so forth. Those arguments have wormed quite deep into the whole 'feudal transformation' historiography and I'd like to be up to date in revising interpretations that partly rest on White's work, especially where it relates to iron production.

Thank you, Tim. I (predictably) enjoyed that, as I thoroughly enjoyed the book itself, my copy of which arrived a week ago (I actually *ordered* two copies, one for myself and one for a "benighted friend"). Since your last post I have been wondering what your response to "God's Philosophers" would be - I thought you might have rather more reservations than to turn out to have.

Are you by any chance coming along to the Routiers' bash on Saturday?

Exactly what would you like to know about medieval iron production?

Glad you liked the review Andy. No, I won't be able to make it to the bash on Saturday, but say hello to the chaps for me.

Re White and stirrups: Essentially there has been a major re-think on the advantages stirrups give in combat and White's idea that they made shock cavalry possible is no longer accepted. The Romans, the East Germanics and the early Franks all had shock cavalry and it's now clear that Roman "horned saddles" and the high-cantled, high croppered steppe saddles that the Germanics inherited from the Alans and Sarmatians also gave them the ability to field heavy lancers before stirrups appeared.

Stirrups do give an advantage, but not as much as White assumed. It might sound strange, but the main benefit stirrups gave was in mounting the horse. This is not exactly trivial when you're wearing a mail shirt, greaves and helmet - try getting on a horse in that gear without using the stirrup and you'll see what I mean. So if you have a unit of heavy cavalry and you want to deploy them quickly it helps that they can all get into the saddle in seconds and you don't have to wait for all your heavily armed guys to find someone to give them a hand up into the saddle. Or to find a convenient stool.

The idea that heavy cavalry led to fuedalism also doesn't really work. Wickham's book details how this was more to do with the politics of patronage and land rewards than the "technological determinism" that White's thesis depends on.

I quite enjoyed James Hannam’s book. He writes well for a popular level and he give some good accounts of the the works of the natural philosophers. I have not yet seen any reviews by university based medievalist specialists and I look forward to seeing whether they share some reservations I had about this book. I would certainly counter this rather over-enthusiastic review.

I have to say that I did not warm to Hannam’s rather disdainful comments on anyone who did not think the medieval era was full of progress. - a standard introduction such as Robert Bartlett’s The Making of Europe has a much more balanced view of areas where there was progress and areas where they were not. Bartlett mentions on page 155 that the average height of human beings was two inches less at the end of the Middle Ages than it was at the beginning, for instance, and he is good on the brutality of the Normans and some of the so-called Christian conquerors -where land grabs and Christianity went hand in hand (see Bartlett. p.91 on the Baltic Crusade). This was not a happy time for Europe.

Was the church much interested in science at all? Was this not the real reason why it never got round to burning anyone? The church was quite ready enough to deal with those who challenged it theologically and one can hardly see the achievements of the natural philosophers as threatening to the church. So long as they minded their business in the Faculty of Arts in Paris, they could get on with it - but when they got too close to theology they were in trouble. The scope of the natural philosophers was overall quite limited and only publisher’s hype can call the Middle Ages the foundation of modern science - you might give it some credit in fields such as the mathematical sciences, optics,etc but even then the ways that these were conveyed through the sixteenth century into later generations is not clear cut. The sixteenth century saw an opening up of important areas of science for the first time since the ancient world but Hannam seems to know nothing of this. He also says virtually nothing about the most progressive part of Europe in this period, Italy. I had to reread his extraordinary comment that humanism was only concerned with the analysis of ancient texts. He may be a medievalist but he should not show his ignorance of humanism quite so abruptly ( if he berates those who do not share his views about the Middle Ages, it does not do him much good to show that he is equally ignorant of the period afterwards - better to keep his mouth shut!) So while there is much to enjoy in this book, I would not expect to see it endorsed by mainstream medievalists or historians whose interests are broader than the Middle Ages but I shall wait and see.

I have to say that I did not warm to Hannam’s rather disdainful comments on anyone who did not think the medieval era was full of progress.

He says nothing of the sort. He simply points out that the common misconception that it was a period largely without significant progress is wrong.

a standard introduction such as Robert Bartlett’s The Making of Europe has a much more balanced view of areas where there was progress and areas where they were not. Bartlett mentions on page 155 that the average height of human beings was two inches less at the end of the Middle Ages than it was at the beginning

Really? Where? Everywhere in the whole of Europe? On average? In one place? This sounds like nonsense - does he give a reference for this remarkable assertion?

he is good on the brutality of the Normans and some of the so-called Christian conquerors

And the relevance is this to the topic of advances in science and technology would be what, exactly?

Was the church much interested in science at all?

Are you sure you even read the book? What were all those churchmen doing studying natural philosophy if "the Church" wasn't interested in it? Who do you think made up "the Church"?

The church was quite ready enough to deal with those who challenged it theologically and one can hardly see the achievements of the natural philosophers as threatening to the church. So long as they minded their business in the Faculty of Arts in Paris, they could get on with it - but when they got too close to theology they were in trouble.

A point that Hannam makes very clearly. He also shows that the scope for natural philosophy was still substantial and theology barely restricted its examination at all.

The scope of the natural philosophers was overall quite limited

That is total garbage.

The sixteenth century saw an opening up of important areas of science for the first time since the ancient world but Hannam seems to know nothing of this.

Because what happened in the sixteenth century was not "for the first time since the ancient world", as Hannam clearly shows.

I had to reread his extraordinary comment that humanism was only concerned with the analysis of ancient texts. He may be a medievalist but he should not show his ignorance of humanism quite so abruptly

Then before you get too snippy, perhaps you should re-read what he actually says. He's quite correctly differentiating between what the word has come to mean from what it meant at the time.

I would not expect to see it endorsed by mainstream medievalists or historians whose interests are broader than the Middle Ages

All the reviews I've seen so far have been positive. Your problem seems to be that you're having some trouble letting go of some irrational prejudices about the Medieval period. You also don't seem to have understood much of what Hannam said.

"only publisher’s hype can call the Middle Ages the foundation of modern science"

I take it you are unfamiliar with Edward Grant's 'The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages'. Your sentence should read:

'only publishers hype, and Edward Grant, one of the most distinguished historians of science, former president of the history of science society and winner of the George Sarton Medal can call the Middle Ages the foundation of modern science'

...but then it kinda loses it's force.

I have seen a number of reviews of this book and several of them make very similar comments that I do about Hannam’s tone. Many of the more positive reviews start off with something on the lines that:’ Many people think the Middle Ages was dreadful. Of course we civilized people don’t and James Hannam has set the others right.’ Whatever the book is really about, this is the impact it seems to have had on reviewers, especially on Amazon, although none of them seem to be medievalists. (The book seems also to have got rather embedded in ‘ We Catholics are right’ debates.) Most medievalists I read don’t get bogged down into whether the Middle Ages were progressive or not - they are much more interested in describing how it actually worked - or failed to work - as a functioning society. I think Hannam glossed over a lot of problems involved in establishing new ideas within the church. I would recommend Brian McGuire’s Jean Gerson and the Last Medieval Reformation , 2005, as a more balanced and probing study of the relationship between Paris University (and Gerson as a Chancellor desperate to bring reform to the Church) and the Church. It is worth reading alongside Hannam to show how much more complex things were than Hannam suggests. The more I read about the medieval church the more I find its relationship with learning hit and miss and it is difficult to argue that it provided a coherent base for the encouragement for learning when so much energy was lost in infighting. Hannam also has a tendency to ignore the vast amount of learning that went on outside the church, especially in Italy.

If you discussing the birth of modern science, you must make some sort of overview of the period after the Middle Ages to show how the achievements of the Middle Ages actively caused the next developments in science. Sorry, but I don’t think Hannam succeeded here (although I found his comments on the later use of Buridan interesting) and his comments on humanism did not help. The humanists were dismissive of the scholastics but they also had major intellectual achievements of their own that had their own impact on the scientific revolution. It was one thing for the likes of Oresme and Buridan to make what , I think most people would agree, were impressive advances ( I have no quarrel with Hannam here) - it is another to argue that they acted as a springboard for something as wide-reaching as ‘modern science’.

Bartlett references his sources for the decline in height on p. 353. - he relates the drop in height ‘as one of the consequences of a change in diet stemming from a shift towards arable agriculture.’(p.155, The Making of Europe).

It is a pity debates on this blog seem to become so aggressive. There are others than myself who have got some enjoyment out of Hannam’s book without being convinced by it - see a review in The New Humanist that is on line- and there may be more when the mainstream medievalists become involved. It is a pity that our sincerely held views are treated as if we were the worst sort of heretics.

Part Two.

I have googled Grant's latest book on Religion and Science to 1550 and someone has put a broadly positive, four star review of it on Amazon. The review suggests that Grant did not argue that medieval science was related to modern science and he made the point too that Grant did not seem interested in Italy. But how can anyone writing about intellectual life not be interested in Italy when half the universities of Europe were based there and in so many areas of life (e. literacy) it was way ahead of the rest of Europe? So I would have my qualifications about Grant as well!

Sorry, gonna do a Freeman.

A few point for booklist:

1) Yeah, GP is for popular rather than academic consumption. The myths it attacks are prevalent and dealing with them is a necessary first step before moving on to subjects that scholars are looking at;

2) Humanist influence in the the physical sciences was almost entirely negative. It's true they had positive effects elsewhere, but that is hardly the point of GP. Lot's of people have been getting very confused about this.

3) I think you are confusing learning in general with science in particular. For instance, Gerson complained that his fellow theologians were spending too much time on natural philosophy (he's quoted but not named in GP IIRC). But he championed other forms of learning. GP is about science and tech, not literature or even theology.

4) About a third of GP is about the period after the Middle Ages. It ends in the 1640s. This is precisely to demonstrate the effect of medieval advances on later developments.

5) Thanks for looking up Bartlett. His point, of course, is that agriculture changed markedly as set out in chapter one of GP. We see similar changes in stature when moving from huntergater to agarian socities;

6) Academic infighting is still taking up a lot of people's energies in the universities. Nothing new there.

Best wishes

James

This is Tim o’ Neil’s blog so you should be prepared to be slapped around a bit.

We are talking about the historical development of natural philosophy, not something as broad brushed as ‘intellectual life’. Hence if we are discussing something like ‘the establishment of new ideas in the church’ then we should restrict them natural philosophical ideas, not something like Jean Gerson’s attempts to found theology on nominalism which, interesting though it is , is not relevant. The fact is that the medieval church did provide a coherent base for learning through the foundation of the universities. This was the first time in history that an institution had been set up for the teaching of science, natural philosophy and logic. It was the first time that an extensive four to six year study in higher education was based on a fundamentally scientific curriculum with natural philosophy as its most important component. Most remarkably, this was the core curriculum for all students and was the pre-requisites for entry into the higher disciplines of law, medicine and theology. Often we find that the infighting you mention did spark debate and even conservative backlashes such as the 1277 condemnations have been argued as having a positive effect.

Humanism is a mixed bag in my opinion. One can for example look at an important figure like Copernicus and see that he was heavily influenced by the movement, including such elements as hermeticism. There was a fruitful emphasis on mathematics, a resurgence of interest in Plato and the revival of texts by authors like Lucretius and Archimedes. Through humanism authority was transferred away from the university to create a new class of intelligencia. However the search for the purity of ancient documents led to the destruction of vast numbers of manuscripts and with them many of the advances made in the Medieval period. So it’s an ambiguous legacy in my opinion.

Charles Freeman’s review of Grant’s book (which you cite) I think is a bit unfair in it’s critical remarks (although he gives the book a high score). Grant could have focused more attention on Italy but his book only goes up to 1550 and the apogee of Medieval science undeniably took place at the universities of Paris and Oxford. He argues that too much natural philosophy was concerned with meeting the challenges of Christian dogma, but this is to miss the point completely. It was precisely the convoluted and often incomprehensible (to my modern temperament) discussions of obscure theological points which often sparked programmes of investigation and led to advances. Angels look utterly ridiculous now, but they were in keeping with the idea of primary and secondary causation, that God works through secondary causes, at first semi-divine beings and later ‘forces’. Actually I’m writing something on this for the blog if you are interested. It’s also not true to say that the development of spectacles represented the ‘application of scientific thought to everyday lives’ rather they reflect the thriving glass industry of Pisa in the 14th century and the fruits of trial and error. They did not spring from any of the advances in Optics made by Alhazan and Roger Bacon.

As for continuity vs scientific revolution, before I read Hannam’s book (and Grants) I was more on the ‘scientific revolution’ side of the spectrum. I think however that the development of the universities and the emergence of theologian-natural philosophers were critical foundations for what followed in the 16th and 17th centuries. By the end of the Middle Ages (1400) the total mass of scientific knowledge was much greater than it had been at the end of the Roman empire; an institutional home had been created for natural philosophy; scholasticism had created a disputative inquisitive kind of intellectual culture; important questions had been formulated and progress had been made towards answering them. This allowed natural philosophy to develop in ways which had not been feasible before.

Booklist,

I don't want to put the boot in, but you say that "Hannam also has a tendency to ignore the vast amount of learning that went on outside the church, especially in Italy."

It's worth pointing out, I think, that the church does not consist only of the clergy, but of the whole body of believers. All work going on in medieval Italy, of any sort whatever, was done by members of the church (unless you are referring to Islamic scholars in Norman Sicily - I don't know of any notable ones, though).

It it very interesting, in fact, that so much work in natural philosophy was, in fact, done by clergymen, even after there was a plentiful supply of university-educated laymen (from, say, the late thirteenth century on). It is, after all, not their primary role, but they evidently saw it as a hugely valuable adjunct to that role.

Lateran Council 1215. ‘There is no salvation outside the Church’ . The options were a bit limited!

My point about Italy is that I think Hannam’s book would have been strengthened if he had included much more about the Italian universites. They were sponsored by the city communes and much more practical and vocational in their approach. Hannam’s claim , p.338, that the universities were primarily intended to educate prospective members of the clergy’ did not apply to the Italian universities. Thy were primarily intended to meet the administrative (e.g. law) and welfare needs of the cities. They did also provide the education of some of the finest minds of the Middle Ages. Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas and Nicholas of Cusa were all educated in Italy before they came to Paris, so was the radical Marsilius of Padua. So one would expect a chapter or two on the Italian city states and their universities, especially in medicine which surely counts as science! The Italian city states,many with strong anti-papal factions -the Ghibellines- also often ensured that the church did not control their lives. 'We are Venetians first and then Christians' as the famous quote goes and one needs some serious examination of the ways this affected what they were able to achieve scientifically, especially in the adoption of innovation without which scientific advance is limited.

Apart from quibbles over ‘ the enormous increases in agricultural productivity and improvements in living standards ‘ in the Middle Ages - for which there seems no statistical evidence - many experts think the opposite might have been the case and it has been argued that living standards did not reach those of the Roman Empire until c.1600- I still can’t see how the Middle Ages provided a great deal to ‘modern science’. There were important advances in the study of the natural world in the sixteenth century -geography reappears as a discipline for the first time since Ptolemy, and the classification of plants, etc also revives- all vital for ‘modern science’. And where is Francis Bacon - limited to to a couple of grudging mentions! These omissions, and the fixation on Galileo, makes the overall argument in the last chapters for the Middle Ages as the founding base of ‘modern science’ in this book weak. Hannam would have made his argument stronger if he HAD followed the Italian experience through but perhaps this would have made him consider the sixteenth century more generously!

We would all have our moments when ‘modern science’ began. Personally I would go for 1800 and use Richard Holmes’ marvellous The Age of Wonder as my proof text!

I'm beginning to get a little confused about Booklist's comments. It almost looks like he hasn't read the book he is criticising, like bookworm admitted. Perhaps they are the same person.

Some oddities in Booklist's comments:

There is plenty on medicine in GP and much of the material discussed is specific to the Italian universities of Bologna and Padua;

There is also plenty on the importance of the rediscovery of Ptolemy's Geography in the early 15th century (not the sixteenth);

The point that the Venetians only obeyed the Pope when they felt like it is explicitly stated.

So please, could booklist read the book before he casts judgement on it? I'm sure he would expect no less from people who might comment on his own books.

Best wishes

James

Tim, thankyou for the stirrups update, that more or less fits with what I'd read elsewhere. As to iron-working, well, one of the arguments in the supposed feudal transformation is that improved agricultural technology helped increase yields, and that this was in part down to an increased use of iron tools. This is apparently based on White, but I've never understood it as it's my understanding from other work that the blast furnace is a fourteenth-century innovation, so it's hard to see why iron tools should have been any more prevalent than they were before (unless there was already more surplus in the system with which to buy them). That's where I'd appreciate input from your readers!

I'd add that I do agree with booklist that the moment when modern science actually began is more probably in the 19th century than the 16th or 17th.

There are earlier blast furnaces than the fourteenth century. The Lapphyttan finds carbon-date to between 1150 and 1350, but we have english record of swedish export of cast iron "osmond" balls from the mid - 13th century, and possible records of the same osmonds in Novgorodian records around 1200. The Noraskog site, which might date to around 1100, was also interpreted by Wetterholm (1999, ISBN 91-7668-204-8) as a blast furnace site.

That being said, the blast furnace is no prequisite of increased iron production. That can be accomplished by intensifying labour.

As I said in my first blog, I am waiting to hear how medievalists assess this book. I have read the book as will be clear from some of the comments and page refs. For instance, I only learned of Nicholas of Cusa's background in Italy from it ( I only knew of him from his work as papal legate in Germany), and noted the two grudging comments on F. Bacon when I failed to come across him in the closing chapters.I also fully approve,as already said, of what Hannam has to say about Oresme and Buridan.

I had a library copy which is returned. I stand to be corrected,not having a copy in front of me,but I believe I was surprised that there was not a single mention of the medical school at Salerno (10th-13th century) This initiated my concern that Italy was badly done by. I have gone back to the Grant review and been directed to another by the same author on Philip Jones, The Italian City-States, that seems to support my thesis.It still remains the case that nowhere was there an analysis on why Italian universities were very different , and in many ways more successful, than Paris and Oxford - which had become pretty stagnant by the end of the Middle Ages.

Alas, I wish I could get publishers to take the interesting ideas I have for books - I have just had another turned down- then I would have the luxury of complaining about reviewers! Hannam is lucky to have got published in a very competitive market and have found a niche for his book. But he can't expect not to be challenged on his thesis.

I do agree with what Booklist says about agricultural productivity in the Middle Ages. For my sins I once did a study of medieval agriculture as part of a history degree. The whole class was bewildered by the mass of imponderables rooted in an almost complete lack of evidence. Certainly ,if Booklist quotes correctly, Hannam's comment seems to be wishful thinking.

That being said, the blast furnace is no prequisite of increased iron production. That can be accomplished by intensifying labour.

Indeed, but that seems to me to presuppose a demand, in which case the iron production can't be an original cause. But then very little of the supposed transformation will fit into nice logical cause-and-effect anyway because it's all happening together... Thankyou for the Wetterholm reference, that has led me to useful things. I'll stop being a knowledge vampire now.

Bookworm/Booklist said:

As I said in my first blog, I am waiting to hear how medievalists assess this book.

You've got no shortage of them here and they all endorse Hannam. If you think other Medievalists are going to think otherwise , you're even more deluded than your meandering and rather muddled posts have already indicated. We've already directed you to Grant's seminal book on the subject, which you tried to dismiss, amusingly, by reference to an Amazon.com review by none other than Charles Freeman. Read the earlier posts on this blog to work out why a review by that bumbling amateur ideologue carries no weight.

And Grant is hardly alone - you can also read Lindberg, Numbers or Crombie or pretty much any other modern historian of science (rather than generalist writers on the Renaissance etc) who are agreed that the Medieval scientists laid the foundations of modern science. It's not like Hannam came up with this - it's commonplace, mainstream stuff.

And pretending to be a new poster while getting the book out of a library to skim read it doesn't exactly give you any shreds of credibility. How about you stop wasting our time and go away now.

Goodbye.

Anon

Of course, evidence is a bit thin of the ground but we do know for example, that the European population surged in the 1100s. It is very difficult to estimate what the population of Europe was in the Middle Ages, but scholars have suggested that it doubled in that century. It may even have quadrupled in a very short period of time. Partly this was due to the so called 'medieval warm period' but it must also have had something to do with the improvements in technology documented.

As for the drop in height, this is to be expected in the transition to an overwhelmingly agrarian society. For example skeletons from Greece and Turkey in late Paleolithic times indicate an average height of 5 feet 9 inches for men and 5 feet 5 inches for women. With the adoption of agriculture, the average height declined sharply; by about 5,000 years ago, the average male was about 5 feet 3 inches tall, the average woman, about 5 feet. So a drop in stature is precisely what we would expect to see.

In terms of GDP per capita, perhaps the best estimates were given by Angus Maddison. He argues that circa AD 400, average per capita income was roughly equal to its minimal subsistence level throughout the world. However, by 1500--before the great opening of the 16th century--Western Europe had nearly doubled its per capita income, while other regions remained stagnant. Maddison also estimates that western Europe's per capita income surpassed China's at around AD 1300.

From a Review of Maddison's work by Andrew Sharpe.

Maddison's estimates of GDP per capita provide fascinating insights into the rise and fall of nations as world leaders in GDP per capita. His GDP per capita estimates back to 1500 allow the identification of world income leaders (Figure 1). During the first two-thirds of the sixteenth century (and before), Italy was the richest country in the world, with a GDP per capita of $1,100 (1990 international dollars), well above that of its closest rival, the Netherlands ($754). In about 1564, the Netherlands overtook Italy and remained the world leader until about 1836, a very long stretch. It was replaced by the United Kingdom. Two-thirds of a century later, around 1904, the United States replaced the United Kingdom as leader, a situation that continues today.

Maddison estimates that GDP per capita in 1000 was lower in western Europe ($400) than in Africa ($416), Asia excluding Japan ($450), and Japan ($425). Indeed, Maddison estimates that western Europe actually regressed during the first millennium, with per capita GDP down from $450 in A.D. 0.

In about 1500, western Europe started to grow, while the other parts of the world stagnated. Maddison explains the exceptionism of western Europe's long-run economic performance, which has continued to the present, by the West's superior technological progress. This includes the development of navigation, military technology, banking, accountancy, marine insurance, improvements in the quality of intellectual life with the development and spread of universities, and the introduction of the printing press.

Yes, that doesn’t contradict what I said. That we start in AD400 at a subsistence level before recovery between the years 1000-1500. You can read Maddison’s ‘The World Economy – A Millennial Perspective on google books. What he does say is that ‘between 1000 and 1500, Western Europe’s population grew significantly faster than those bordering the Mediterranean’. ‘The urban proportion rose from zero to 6 percent, a clear expansion in manufacturing and commercial activity’. The main areas of growth were Flanders and the Italian City States.

He also gives life expectancy in the England of 1301-1425 as 24.3, which is actually the same as that of Roman Egypt from 33AD-258AD. By 1541-56 it was 33.7. The Western European population in 200AD (in 000’s) is estimated at 27,600. This fell to a low of 18,600 in 800AD. By 1000, it was back up to 25,413, not quite at it’s peak in 200AD. However by 1200, the population had leapt to 40,885, by 1300 it had reached 58,353. Even after repeated attacks of plague the western European population was maintained at 41,500, well above what it had been in 200AD

On page 42 you will see figure 1-4 ‘Comparative Levels of GDP per Capita: China and Western Europe 400-1998AD. This shows that Western Europe overtook China in 1300.

“In about 1500, western Europe started to grow, while the other parts of the world stagnated.”

This part of the review is wrong. For 1000-1500 Madison gives an average compound growth rate of per capita GDP of 0.13. He writes that ‘west European income was at a nadir around the year 1000. It’s level was significantly lower than it had been in the first century..there was a turning point in the eleventh century when the economic ascension of Western Europe began’.

Came across this debate= probably too late to contribute. We would not say the population growth in the modern world was a sign of progress - surely the problem with the Middle Ages was that it grew faster than resources did and living standards may have fallen in many areas. Hard to assess evidence of rising income-one has to balance out the big rises in Italy against the stagnation in many other parts of Europe. I think everyone agrees that one cannot generalise about medieval Europe as the experience of different parts was so different, and conditions changed so much from century to century. I haven't read Maddison- does he discuss this differentiation in the way that virtually every other introduction to the Middle Ages does? The extracts given here leave this unclear but I can't believe he would be so naive as to attempt to give Europe-wide figures without massive qualifications.

surely the problem with the Middle Ages was that it grew faster than resources did and living standards may have fallen in many areas.

"Surely"? Evidence please. This doesn't fit with anything I've come across in relation to the period. All the evidence I know of indicates steadily rising living standards thanks to greater and more efficient and effective use of resources.

Hard to assess evidence of rising income-one has to balance out the big rises in Italy against the stagnation in many other parts of Europe.

Pardon? "Stagnation" where, exactly? In "many parts of Europe" such as where, precisely? What the hell are you talking about?

One can start with the summing up of the period 1350- 1450 in George Holmes', Europe Hierarchy and Revolt, his Chapter Three,'Economic and Social Forces' (Oxford ,2000). Holmes was a deeply revered Oxford authority on the Middle Ages and sixteenth century. He writes:

'A number of historians have described this period as an age of 'contraction' or 'depression'. The general phenomenon appears in a variety of widespread manifestations, some of them basic economic and social features - decline in population, decline in the volume of trade, contraction of areas under cultivation - and some more complex social changes such as decline in the authority of the nobility over their tenants, social revolutions by the lower classes, . . .This is the only period in the history of Europe, at least since the Dark Ages, for which historians would postulate a general and prolonged contraction.' (pp. 77-9)

My reason for entering this debate was that generalisations about the Middle Ages as a whole seem most unhelpful but I can't believe that Tim O'Neil has never read ANYTHING that contradicts his rosy views on the Middle Ages. Where has he been living? I only dropped in on this debate by mistake but if I had the time I could provide him with acres of material that show that in particular areas of Europe things went down hill, that peasants suffered declining standards of living as landowners tightened their systems of control. Likewise I can provide evidence from other areas of Europe where things genuinely did seem to get better- this is usually related to the growth in trade routes. There is no point in providing all these as they can be found in any chapter on social and economic conditions in medieval Europe - I can't think offhand of any medieval historian who gives an unqualified thumbs up for the medieval economy over the years,say, 1100-1500, except possibly in commerce, industry. This is largely because agricultural technology was not sufficiently advanced to be sure of beating the climate,etc and so when things like 'The Little ice Age'/ Black Death happened there was not much that could be done about it.

One can start with the summing up of the period 1350- 1450 in George Holmes

That's fairly accurate summary of that particular century overall. Unfortunately that doesn't help you when it comes to backing up your statements about the rest of the 900 years that make up the period overall, especially the period of remarkable growth and development from 1100 till the early Fourteenth Century. Nice use of neatly selective evidence there.

I can't believe that Tim O'Neil has never read ANYTHING that contradicts his rosy views on the Middle Ages.

Don't be absurd. I simply asked you to justify some sweeping generalisations that you made in your last comment. How the fuck does that unremarkable request suddenly mean I have some kind of "rosy view" on the period?

I can't think offhand of any medieval historian who gives an unqualified thumbs up for the medieval economy over the years,say, 1100-1500, except possibly in commerce, industry.

Yes, because it's not like they mattered much.

so when things like 'The Little ice Age'/ Black Death happened there was not much that could be done about it.

If those things hit us NOW there'd be not much we could do about them. So what exactly are you saying?

Menedemus, you mention the century from 1350 as one characterised by fall in population and decline in volume of trade and area under cultivation.

That would be the period immediately afer the black death, no? Yes, in the face of that onslaught the population halved (I'm using a broad brush, OK?), and the survivors neither need to nor had the resources to cultivate as much land as they had formerly, nor did they need the same volume of trade goods (did the volume per capita go down, after the immediate years of the plague when people avoided travel?). What they did do in subsequent decades, to maintain their standard of living, was to accelerate the processes already under way of urbanisation and mechanisation. With manpower suddenly less available, machine power was substituted.

The point is that pointing at the second half of the fourteenth century as indicitive of what things were like in the middle ages generally is rather like pointing to, say, 1916-1919 as representative of the industrial age. Both are episodes that can't be ignored, but neither is typical.

I wanted to make a single point - that the sweeping generalisations about the life in Europe in the Middle Ages are not helpful. Different parts of the continent had very different experiences and different periods saw very different outcomes. The century 1350-1450 (somewhat longer than 1916-19) cannot be passed over as a mere blip- it was part of the integral experience of Europe in the period 1000-1500 and even here there were still growth areas, as I said in my original posting. This website seems to have a bias that the Middle Ages have to be talked up instead of being analysed in their own terms.As such one wonders whether it is of much use to those with a general interest in medieval history. I am off elsewhere!

I wanted to make a single point - that the sweeping generalisations about the life in Europe in the Middle Ages are not helpful.

And in doing so you made some generalisations of your own. And ones that demonstrated a lack of knowledge of the period. This is why people are disputing what you're saying.

The century 1350-1450 (somewhat longer than 1916-19) cannot be passed over as a mere blip- it was part of the integral experience of Europe in the period 1000-1500

Really? So you'd better go explain that to Gerald A.J. Hodgett. Because in his A Social and Economic History of Medieval Europe - pretty much a standard text on this kind subject - he dedicates a chapter to "Economic Growth in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries" (pp. 88-106), which follows chapters detailing the steady economic growth across Europe in the preceeding centuries. He follows it with a chapter entitled "Decline and Change" on the century you oh-so-selectively decided to pick as being typical. It was nothing of the sort.

This website seems to have a bias that the Middle Ages have to be talked up instead of being analysed in their own terms.

Bullshit. This blog has a bias towards proper research and an objective understanding of history.

I am off elsewhere!

I can't say you'll be missed.

Damn

I missed the fun. As it happens, in 'Europe, hierarchy and revolt' George Holmes wrote.

"In the next century, extending from around 1350 to around 1450 most historians have discerned a fundamental break in the development of Europe. A number of historians have described this period as an age of 'contraction' or 'depression'."

So he was referring to a single century in which Europe was hit by famine and the repeated return of the Black Death.

In the introduction he writes:

"In 1300 Western Europe was probably already by far the richest part of the world if wealth were measured by head of the population. Most of the wealth was concentrated in a band running along the continent from south-east England to northern Italy including northern France, the Netherlands and the Rhineland."

You're doing wonderful work here. I don't know if you are keeping a tally or not, but consider this myther converted!

I was wondering if you might have a suggestion for a skeptic's guide to history, or something along those lines, something to give a sheepish laymen the key to exploring historical terrain without further erroneous conclusions. These topics are very fascinating, and I think you would agree, very relevant, I just don't know where to start.

Thanks in advance, and keep up the good work!

Lee asked:

I was wondering if you might have a suggestion for a skeptic's guide to history, or something along those lines

A few that spring to mind:

Ronald L. Numbers, Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion tackles myths about science and religion used by both religious and anti-religious propagandists and is definitely the kind of thing you''re looking for.

Stephen Harris & Bryon L. Grigsby (Eds), Misconceptions About the Middle Ages covers specific myths about the Medieval period; everything from the period being one where lots of witches were burned to the existence of chastity belts.

Regine Pernoud's Those Terrible Middle Ages: Debunking the Myths is a lengthy essay doing the same thing, though from a more French perspective.

That should help.

I actually disagree with several points:

1. The "Jesus never existed" is not just an Internet idea; it's been at least a semi-serious item of discussion for more than a century. I personally give it a 10 percent chance of reality, at least.

2. Not all the Greek learning was "new" to late medieval Europe. Aristotle was never totally forgotten and in medicine, Galen never was at all, sadly.

3. The medieval period, per most historians, ended before the 1500 CE the author uses as a cutoff.

4. As for no medieval persecutions? Abelard and Heloise, even if orders didn't come from the top, were persecuted as much if not more for their thinking than for their love. (That said, of course, they were philosophers, not scientists.)

Overall, this is not a bad post, but, having read O'Neill before, it's not the first time he's gotten several things wrong, incomplete, or straw-manned himself.

An idiot wrote:

I actually disagree with several points:

Gosh, really?

1. The "Jesus never existed" is not just an Internet idea; it's been at least a semi-serious item of discussion for more than a century.

I didn't say it was just an internet-based idea and was referring to the fact that most of its current proponents propagate it on the net. As opposed to doing so in peer-reviewed journals and in academic conference papers, for example. And I'm quite aware of the history of this silly idea, thanks.

I personally give it a 10 percent chance of reality, at least.

That's nice. Almost no actual scholars do.

2. Not all the Greek learning was "new" to late medieval Europe. Aristotle was never totally forgotten and in medicine, Galen never was at all, sadly.

I didn't say it was. If you'd bothered to actually read the review carefully rather than trying to find things to nitpick you'd have noticed I mentioned Boethius' translations of Aristotle's works of logic as an example of some of the Classical learning which survived in the early Medieval period.

3. The medieval period, per most historians, ended before the 1500 CE the author uses as a cutoff.

Various cutoff dates are used, most of which are fairly arbitary. 1500 is very commonly used and you'll have a hard time substantiating your use of the word "most" in the sentence above.

4. As for no medieval persecutions? Abelard and Heloise, even if orders didn't come from the top, were persecuted as much if not more for their thinking than for their love. (That said, of course, they were philosophers, not scientists.)

Yes, they were. But what you say is complete and utter garbage anyway. Their learning had nothing to do with it.

Overall, this is not a bad post, but, having read O'Neill before, it's not the first time he's gotten several things wrong, incomplete, or straw-manned himself.

You're an idiot. And how the fuck does someone "straw-man themself, you moron? Go away.

I liked this book, but I feel there is one area that Hannam could have covered in more depth, and one that is also too often sadly ignored. That is the role the Byzantines played in the growth and development of Medieval sicnce and technology. Admittedly Hannam was constrained by space, and the level of his own research. but I really think this topic deserves to be more widely publicised.

From the limtited research I have done it appears that a number of the innivations which are usually attributed to the 'Arabs' were actaully of Byzantine origin, or the Byzantines were developing them at about the same time. I think they are not given anywhere near as much credit as they are rightfully due . Could it be because they were Christians?

gadfly, I always got the idea that the reason why Abelard and Heloise were persecuted 'for their love' was because;

1. Abelard was a priest and was not meant to be 'fooling around' with women.

2. He betrayed the trust of his patron and employer by having sex with his niece when he was meant to be 'teaching' her.

To draw modern parallels, what Abelard did would be like a teacher or lecturer today having an affair with one of their students. Such a person they would probably lose their job and likely get sent to prison when they were found out, even today, so what is your logical basis for calling what happened to Peter Abelard ‘persecution’ in this sense?

I think your view of this subject is based on modern sentimentality and judgements of the past (and likely some play or movie which totally misrepresents the events). I suggest you research these things more and get your facts right.

"Just because persecution wasn’t as bad as it could have been, and just because some thinkers weren’t always the nicest of people doesn’t mean that interfering in their work and banning their ideas was justifiable then or is justifiable now."

I found that hilarious. The very same things are being done today to scientists who do not accept the popular theories and seek to do research counter to them (evolution). Atheists are such grand hypocrites.

The very same things are being done today to scientists who do not accept the popular theories and seek to do research counter to them (evolution).

Don't be ridiculous. No-one is "banning" the work of anti-evolutionsists or "interfering" with it. They are simply pointing out that it's scientifically flawed and motivated by ideological bias rather than reason and evidence. Please take the "Christians are persecuted!" crap back to Fox News and Bill O'Reilly.

"Don't be ridiculous. No-one is "banning" the work of anti-evolutionsists or "interfering" with it. They are simply pointing out that it's scientifically flawed and motivated by ideological bias rather than reason and evidence. Please take the "Christians are persecuted!" crap back to Fox News and Bill O'Reilly."

I hope you will be able to see the problem with what you just said and how it betrays any attempt at seeming objective on the issue. I did not say Christians are being persecuted. You have equated scientific opposition to a "theory" to Christianity. This, I suppose, allows you to justify the discrimination those who, in the scientific field, oppose the theory receive. I have had this talk a few times with atheists. First they try to deny that people are suppressed, then they will try to justify it once denial has failed. You have justified it to yourself by calling all opposition unscientific and ideological. This is really no different than what an atheist would like to accuse Christians of in the past. One Christian leader could easily say that an atheist pushing the theory of evolution would be driven by unscientific ideology. It is really contingent on the assumptions about reality being made and dominant at the time.

The fact is that many who publicly opposes the theory are ridiculed and may be at the receiving end of tangible deleterious effects in academia etc., if they are in a position for it. Note, I did not say Christians. There are documented cases of this discrimination (that atheists and the like are quite fine with).

This is not particularly related to your article here. That quote just reminded me how inconsistent atheists can be without even seeming to have a clue. Could you even imagine that what you talk about here is actually true of atheists with regard to science and the theory of evolution in particular? You guys are not objective in the least.

This is not particularly related to your article here.

No it isn't. And I have no intention of my blog providing any kind of platform for babbling about "Scientific Creationism" or "Intelligent Design" or whatever it is you people are calling your bullshit these days. Go away.

You list Mr. Bradwardine twice.

No objection to the rest of what you wrote, or at least I don't feel competent.

One remark: later Renaissance appears to be mostly located in areas of Europe different than the 12th century one, or at least I get such an impression. Am I right? Why is it so?

Art and science do not exist in vacuum. Somebody has to pay artists and scientists, and Italy was quite rich.

But there were many achievements in Medieval England, then not a really powerful and rich country. That's a bit surprising for me (so it requires an explanation).

It's quite strange to see how some comments on your article went really emotional, even using words like moron, idiot etc. It does not help spreading knowledge, at least in my opinion.

later Renaissance appears to be mostly located in areas of Europe different than the 12th century one

Not really. The centrers of learning in the twelfth century revival were in Italy, France and England, all of which saw elements of the later revival of Classical art and literature (though virtually no science) that we call "the Renaissance".

But there were many achievements in Medieval England, then not a really powerful and rich country.

Those achievements happened between the twelfth and the fourteenth centuries, when England was very much a rich country (thanks to the thriving wool trade) and part of a wider territory ruled by the kings of England who were also lords of Aquitaine, counts of Anjou, lords of Maine and generally rulers of a large slice of western Europe. The kings of France, who spent most of the fourteenth and part of the fifteenth century fighting for their lives against the English in the Hundred Years War, would disagree with you about the English not being powerful.

It's quite strange to see how some comments on your article went really emotional, even using words like moron, idiot etc.

I give people a chance and am always civil initially. When it becomes clear they are not interested in rational discussion and just want to prop up their biases, I become less polite. Here in Australia we call a spade a spade and tell an idiot he's an idiot. If you don't do this where you come from, that's your business. Feel free to be nice to idiots - I'll keep commenting on my blog the way I choose, if it's all the same to you.

For the name of one scientist burned, persecuted or oppressed for their science in the Middle Ages try

Kazimierz Łyszczyński, burned for opinions he didn't even published.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kazimierz_%C5%81yszczy%C5%84ski

"Kazimierz Łyszczyński"

Wrong on two counts: (i) he was burned for apparently denying the existence of God and not anything to do with science - his views were purely theological and (ii) he was executed in 1689 - that's well after any date generally acknowledged as the end of the Middle Ages (usually c. 1500) Nice try but - fail.

"Kazimierz Łyszczyński"